Joe Bell fights to open cold case records of a 1946 mass lynching

Joe Bell has been engaged in a legal battle to open the grand jury transcripts of a cold case lynching that occurred in 1946. Photo courtesy of Bell, Shivas & Bell.

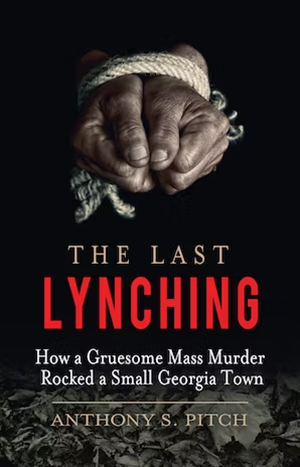

At a 2008 American Bar Association event in Washington, D.C., Joseph Bell Jr., an attorney with a keen interest in discrimination cases, first met author Anthony Pitch, a historian and authority on President Abraham Lincoln.

A friendship developed. Bell, an adjunct at the County College of Morris in Randolph, New Jersey, started taking his students to the nation’s capital on Pitch’s Lincoln tours. On a trip in 2013, Pitch told Bell about his work on a book about the 1946 mass lynching at Moore’s Ford Bridge in Monroe, Georgia—known as the last mass lynching in America. But Pitch was stuck.

“He said, ‘You know, I really would like to wrap the book up by being able to secure the grand jury transcripts of that proceeding,’” says Bell, a founder of Bell, Shivas & Bell in Rockaway, New Jersey.

The conversation about Pitch’s desire to open the grand jury proceedings launched Bell’s 10-year pro bono journey for justice for a decades-old case.

Racial tensions

In 1946, racial tensions in the South were running high. Two years earlier, the U.S. Supreme Court had declared all-white primaries unconstitutional in Smith v. Allwright, which bolstered voter registration of minorities and changed the dynamics of Georgia politics. On July 18, Maceo Snipes was the only Black person to cast his vote in Taylor County, Georgia. Just hours later, he was lynched, shot in the back.

A week later and about 110 miles away in Walton County, Georgia, Roger Malcolm, a Black sharecropper, confronted his white employer, Barnette Hester. Malcolm accused Hester of sexually abusing Malcolm’s wife, Dorothy, who was seven months pregnant. A fight ensued, and Malcolm allegedly stabbed Hester, who was taken to the hospital barely alive.

Loy Harrison (right) stands on the old Moore’s Ford Bridge with Oconee County Sheriff J.M. Bond (left) and coroner W.T. Brown of Walton County (center) after the July 25, 1946 lynching. AP Photo/File.

Loy Harrison (right) stands on the old Moore’s Ford Bridge with Oconee County Sheriff J.M. Bond (left) and coroner W.T. Brown of Walton County (center) after the July 25, 1946 lynching. AP Photo/File.After Malcolm’s arrest, Dorothy asked their friends Mae and George Dorsey for help. The couple went to their employer, Loy Harrison, a white farmer and landowner, who drove the Dorseys and Dorothy to the jail in Monroe, where Harrison posted Malcolm’s $600 bond on July 25. On the way home, Harrison drove the two couples the long way home on an unpaved backroad. As he approached Moore’s Ford Bridge over the Apalachee River, the road was blocked by 15 to 20 unmasked and armed white men. Mae Dorsey recognized some in the mob and called them out.

After Harrison was told to step aside, the Malcolms and the Dorseys were dragged out of the car, tied to a tree and shot more than 60 times at close range. All four died.

“The worst was Roger. His face was likened to shredded wheat,” Bell says.

No one charged

Days after the Moore’s Ford lynchings, protestors marched in Washington, D.C., and the National Association of Colored Women picketed the White House. AP Photo/Washington Star.

Days after the Moore’s Ford lynchings, protestors marched in Washington, D.C., and the National Association of Colored Women picketed the White House. AP Photo/Washington Star.

After the mass lynching at Moore’s Ford, telegrams filled with outrage hit President Harry S. Truman’s desk, motivating him to create the President’s Committee on Civil Rights on Dec. 5, 1946. “This case really is truly a part of American history,” says retired New Jersey Superior Court Judge Paul W. Armstrong.

In the years following the lynching, the FBI and Georgia Bureau of Investigation interviewed 2,790 of Monroe’s 4,100 residents, Bell says. One hundred and six people testified before a 16-day grand jury in Athens, Georgia, in December 1946.

No one has ever been charged for the murder of the victims.

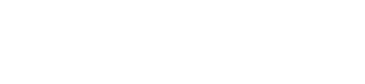

George Dorsey’s coffin is carried out of Mount Perry Baptist Church in Bishop, Georgia, after his funeral. Dorsey was a World War II veteran. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution via AP, File.

George Dorsey’s coffin is carried out of Mount Perry Baptist Church in Bishop, Georgia, after his funeral. Dorsey was a World War II veteran. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution via AP, File.

Bell wanted to help Pitch learn the truth. “I feel that the historical significance of this case is that it is the beginning of the modern Civil Rights Movement in America,” Bell says. “We wanted to shine light on the light of truth upon an appalling injustice: why no one has been brought to justice all throughout the years.”

He knew what he was up against.

Teaching moments

Long before his crusade for justice for the four people lynched at Moore’s Ford Bridge, Bell began his career as a high school teacher in Newark, New Jersey, after graduating from Montclair State College. “I was always intrigued by the law, and wanted to be able to take on cases that perhaps could change society and change the way people live,” Bell says.

While attending Seton Hall University School of Law at night, Bell was elected Morris County clerk. One of his duties was presiding over naturalization ceremonies. “He would invite folks like Yogi Berra, and they would talk about their families and how they had come to America,” Armstrong says. “Now, Joe did all of this at his own expense.”

While in that post, Bell developed a Braille ballot for the blind and a system to enable posting bail with credit cards.

“His personality is so outgoing, so charming, people don’t realize how accomplished an attorney Joe is,” Armstrong adds.

After graduating from Seton Hall, Bell went on to receive an LLM in labor and employment Law at New York University School of Law and began private practice at Dorsey, Pryor and Bell. He has been an ABA member since 1986. He served as municipal counsel and municipal prosecutor before opening his own practice in 1993.

Legal rollercoaster

The Moore’s Ford case brought him into an area of law he’d never practiced.

Cover of The Last Lynching from Skyhorse Publishing.

Cover of The Last Lynching from Skyhorse Publishing.After more than 70 years, no one was sure that the grand jury records even existed, he says. If they did, the court would need to release the records for Bell to review.

First step for the New Jersey lawyer was to be admitted to the Middle District of Georgia. Next, he reached out to U.S. District Judge Marc Treadwell, who said the records were gone—lost, misplaced or subject to a retention schedule, Bell says. The judge dismissed his application without prejudice.

In 2016, just after Pitch’s book The Last Lynching: How a Gruesome Mass Murder Rocked a Small Georgia Town was published, Pitch called Bell. He had located the grand jury transcripts, mismarked in the National Archives and Records Administration outside Washington, D.C.

Just weeks later, Bell argued to the court in the Middle District of Georgia that the Georgia Bureau of Investigation and FBI considered Moore’s Ford a cold case. “The judge felt that the [need for] secrecy was outweighed by the broader historical experience,” Bell says. Pitch was granted access.

Of friend Anthony Pitch (right), Bell writes: “He was a consummate gentleman, always displaying the highest courtesy and dignity to those whose lives he touched.” Photo courtesy of Bell, Shivas & Bell.

Of friend Anthony Pitch (right), Bell writes: “He was a consummate gentleman, always displaying the highest courtesy and dignity to those whose lives he touched.” Photo courtesy of Bell, Shivas & Bell.The U.S. Justice Department appealed to the Atlanta-based 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, but a three-judge panel in a 2-1 vote affirmed the release in 2019. The government asked for the case to be heard en banc. In an 8-4 March 2020 decision, the majority said it would be improper to release the grand jury documents because it could endanger the secrecy of every grand jury proceeding going forward.

Bell was frustrated. “There are cases involving Richard Nixon Watergate tapes, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, Alger Hiss, Jimmy Hoffa—they have released those grand jury transcripts,” he says.

Pressing on

Although Pitch died in 2019, Bell felt an obligation to press on. Undeterred, he appealed the 11th Circuit’s decision to the Supreme Court. But in fall 2020, the court declined to hear Bell’s appeal.

“The Supreme Court decided not to accept [it]—this in the era of George Floyd. It’s something that we still can’t understand,” Armstrong says.

“If you look at the court and the public perception of the court’s role as an instrument of justice, it’s been denied this time,” Bell says. “But we’re not dead. We’re not dead.”

Men exit the Athens, Georgia, building where a federal grand jury was meeting on Dec. 2, 1946, to look into the lynchings of the Malcolms and the Dorseys. Joe Bell has been pursuing the transcripts of those grand jury hearings. AP Photo/Rudolph Faircloth.

Men exit the Athens, Georgia, building where a federal grand jury was meeting on Dec. 2, 1946, to look into the lynchings of the Malcolms and the Dorseys. Joe Bell has been pursuing the transcripts of those grand jury hearings. AP Photo/Rudolph Faircloth.His hope stems from the amendment of the Civil Rights Cold Case Act and a commission that will take a fresh look at the case. Four of the five members have been appointed to the Civil Rights Cold Case Records Review Board, though at press time the commission had not yet met. “We welcome letters from [ABA members] to their U.S. senators to act with dispatch in confirming the fifth member when nominated and expediting the creation of the panel and staff so that the memories of all that were lynched be enshrined by those who are living,” Bell writes in an email.

“Joseph being Joseph—and this going on the 10th year of his pro bono activity—as soon as President Biden finishes appointing members of the Cold Case commission, Joe will be arguing before that cold case commission,” Armstrong says. “[Bell] has come to actually personify the commitment to pro bono advocacy.”

Bell feels a sense of obligation to the legacy of Pitch and the community.

“Joe Bell is sharp, articulate and he knows the law,” says Tyrone Brooks, a former Georgia state representative who organizes an annual reenactment of the Moore’s Ford lynchings. “He’s a godsend to our movement.”

Tyrone Brooks stands on Moore’s Ford Road near the site of the 1946 lynchings. AP Photo/David Goldman.

Tyrone Brooks stands on Moore’s Ford Road near the site of the 1946 lynchings. AP Photo/David Goldman.

Bell’s unanswered questions keep him going.

“Why, oh why, oh why, were four innocent people killed so violently? Why was there such a cover-up? What is there to hide? It’s been 76 years,” he says. “I don’t think you can begin the healing process until we know the actual truth.

“I know that I’ve been defeated in the court battles, but being defeated is often a temporary condition,” Bell adds. “Giving up makes it permanent. And I’m not giving up.”

Members Who Inspire is an ABA Journal series profiling exceptional ABA members. If you know members who do unique and important work, you can nominate them for this series by emailing [email protected].