Sept. 25, 1930: U.S. names its first drug czar

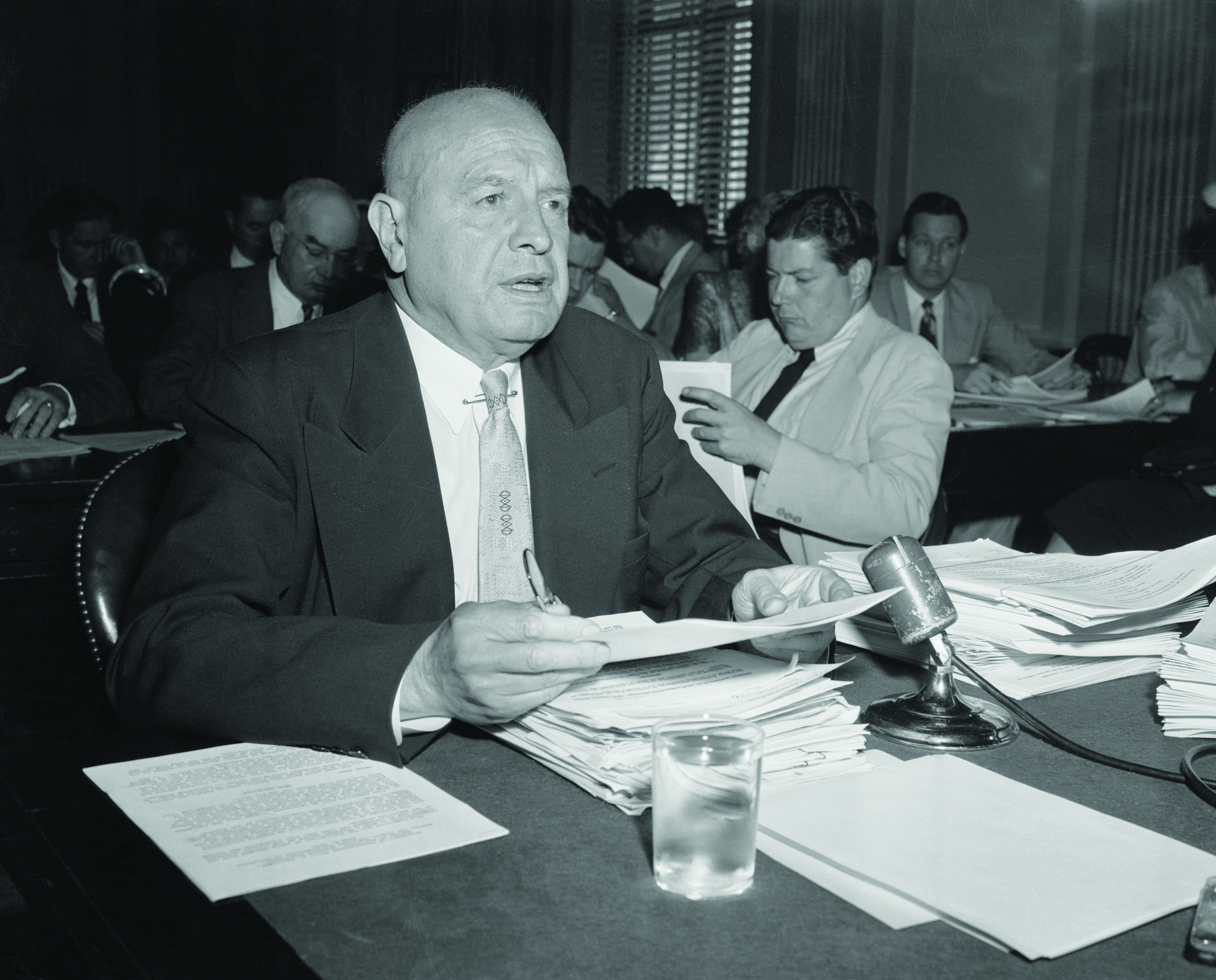

Harry J. Anslinger. (Photo by Bettmann/Contributor)

One October morning in 1933, 21-year-old Victor Licata was found blood-splattered and delirious in a bathroom at his home in Ybor City, Florida. Elsewhere in the house lay his parents, a brother and his sister—apparently bludgeoned to death with an ax as they slept. Another brother, similarly beaten, later died at the hospital.

Licata, who had a history of mental illness, babbled a confession of sorts to local police claiming, among other things, that his family had amputated his arms and replaced them with wooden prosthetics and metal claws. Dubbed “The Dream Slayer” in the local press, he was committed to a mental institution.

Even by the lurid standards of 1930s crime reporting, the murders were sensational. They became more so with the revelation that Licata had used cannabis, which investigators were quick to blame—more than his diagnosed schizophrenia—for the brutality of the crimes.

Even before the end of Prohibition in 1933, public concern about narcotics addiction had been mounting. In the latter half of the 19th century, various opioids and cocaine were used in “patent medicines” and were widely available for sale, with drug laws and their enforcement deferred to the states.

That changed with passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, which required the listing of narcotic ingredients in medicines shipped interstate. The Harrison Act of 1914 took federal involvement a step further, establishing a regime of taxation and regulation that all but prohibited the nonmedical use of specific drugs. But cannabis—officially described as “marihuana” or “hemp”—was not part of any federal enforcement effort until Harry J. Anslinger, the first head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, decided that it should be.

Before his appointment to the post by President Herbert Hoover on Sept. 25, 1930, Anslinger had developed a well-regarded reputation for law enforcement, a career he began as a railroad investigator. He had replaced Levi Nutt, head of the Treasury Department’s narcotics division, after Nutt’s family was accused of having ties to gangster Arnold Rothstein. And in a career that paralleled that of J. Edgar Hoover, his appointment initiated an era of robust federal narcotics enforcement that has lasted for decades.

Ignoring evidence to the contrary, Anslinger regarded cannabis as a dangerous drug with no medicinal value—an unwelcome import by Mexican immigrants and popularized by Black jazz musicians. But an early reluctance to pursue the drug alongside narcotics ended with the passage of the 1937 Marihuana Tax Act, a law modeled after earlier firearms legislation that effectively made the possession or sale of marijuana a federal crime. And, leveraging racial stereotypes and anecdotal evidence, Anslinger pursued its passage—determined to make, and keep, cannabis illegal under federal law. Enter Licata.

As part of his legislative strategy, Anslinger maintained a “Gore File”—a collection of police reports and true-crime stories to support by anecdote the corrupting nature of cannabis. For The American Magazine, Anslinger penned “Marijuana: Assassin of Youth,” an article describing Licata as a “sane, rather quiet young man” crazed by marijuana. In support of the Marihuana Tax Act, he reiterated the Licata murders, alleging before Congress that cannabis was worse than opium: “Opium has all the good of Dr. Jekyll and all the evil of Mr. Hyde. This drug is entirely the monster Hyde, the harmful effect of which cannot be measured,” he testified.

With the act in place, Anslinger’s uncompromising views became public policy, and they remained in place long after he retired in 1962. Even a joint study in 1958 by the ABA and the American Medical Association recommending wholesale review of federal drug policy was dismissed by Anslinger as misguided. And despite a widespread state-level decriminalization that began with California in 1996, marijuana remains a Schedule 1 drug under the Controlled Substances Act.

As for Licata—whose crimes allegedly inspired the 1936 cult film Reefer Madness—he escaped in 1945 from the mental institution where he had been committed.

He was recaptured five years later and confined to Florida’s Raiford penitentiary, where he hanged himself in December 1950.

This story was originally published in the August-September 2023 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “U.S. Names Its First Drug Czar.”