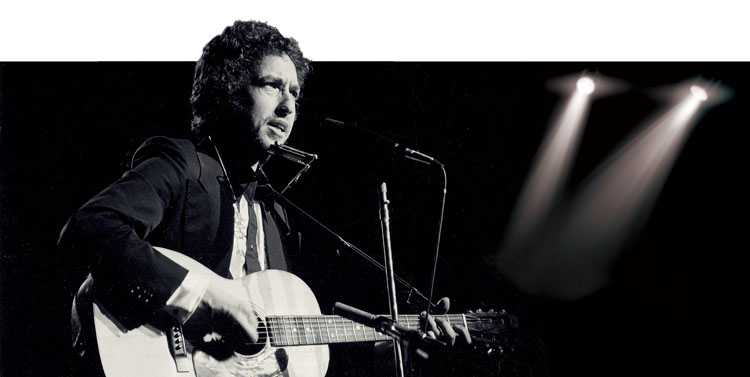

Take a note from how Bob Dylan cleverly retrofits traditional melodies to craft a story

Photo of Bob Dylan by PL Gould/Images/Getty Images

For me, the most important law songs, the ones that are closest to my heart, are often not about lawyers at all but instead about themes of justice and injustice. The most remarkable of these songs are by our two greatest folk poets: Bruce Springsteen and Bob Dylan.

Of the two, I tip toward Dylan as the greater of our troubadour-poets, in part because of the intellectual quality of his lyrics about law and justice and the diverse topicality of his law songs. Also, because of Dylan’s fearless ability to work outside of the rules of pop songwriting, to go beyond constraints and forms of popular song structure, and to shamelessly borrow/steal or adapt pitch-perfect traditional melodies retrofitted to stories and poetic visions about justice and injustice in America.

In the best of his meditations on American justice and injustice, Dylan has an uncanny ability to shift perspectives effortlessly within songs. Like a skilled trial attorney in a closing argument, Dylan often steps outside the story he is telling, as if looking down from a vast distance or back across time upon the events depicted within the songs. He never loses the thread or drive of the narrative, connecting lyrics and melodies with universal themes about law and our longing for justice. Indeed, Dylan’s songs about American justice and injustice have renewed meanings in the dark shadows of our own time.

Two songs from Dylan’s oeuvre—the first an early 1960s story-song, the second a 1980s poetic vision—suggest several storytelling lessons about the art of adaptation that are especially relevant for lawyer-storytellers today.

‘Percy’s Song’

Dylan’s “Percy’s Song” (1963) is a remarkable work of creative adaptation and alchemy. In “Percy’s Song,” Dylan transforms seemingly incongruous narrative pieces: Dylan’s autobiographical material about a friend who was badly injured in an automobile accident, a melody borrowed from an early dark and fatalistic English/Scotch ballad (“The Twa Sisters” or “The Wind and Rain” in Francis James Child’s collection of folk ballads), and a thematic idea about the cold finality of legal judgments, lifted from a different English Child ballad, “Geordie.” (In “Geordie,” a wife pleads unsuccessfully to a judge to spare the life of her husband after he is condemned to death for killing the king’s deer to feed his family.) The borrowed melody, story, lyrics and theme are repackaged in Dylan’s first-person voice, the story reset inside a present-day American courthouse. The formal syntax, structured repetitions and melody from the original English ballad are retained in Dylan’s adaptation.

The sixteen verses (stanzas) of the song tell the story of a nameless friend of Dylan’s who has been convicted of vehicular manslaughter resulting from the deaths of four people in an automobile accident.

A crash on the highway

Flew the car to a field

Turn, turn, turn again

There was four persons killed

And he was at the wheel

Turn, turn to the rain

And the wind

The nameless friend has been, improbably, sentenced to 99 years for manslaughter when Dylan arrives on the scene. In the judge’s chambers, Dylan pleads on behalf of his friend, a good man who “wouldn’t harm a life.” The sentencing judge tells Dylan that he has arrived “too late, too late. For his case it is sealed, his sentence is passed and it cannot be repealed.” Dylan persists in his plea, “But he ain’t no criminal, and his crime it is none ... What happened to him could happen to anyone.” The judge then asks Dylan to leave his chambers. After, Dylan plays the story over and over on his guitar, but he can find no meaning or justice within it.

And I played my guitar

Through the night to the day

Turn, turn, turn again

And the only tune

My guitar could play

Was, “Oh the Cruel Rain

And the Wind”

Thematically, akin to “Geordie,” the story contrasts the finality and severity of legal judgments, applying the king’s (written) law that often can not be reconciled with fundamental notions of justice. A second contemporary theme of “Percy’s Song” is about how fate and chance often shape events in ways that are beyond the law—and beyond our comprehension or understanding.

Some lawyers may dismiss “Percy’s Song” as too obvious or didactic—an unbelievable story about a villainous judge who abuses his discretion in sentencing. But it works emotionally upon the listener, nevertheless. How does Dylan make the story work? He adapts borrowed lyrics wrapped in a stolen melody married to a universal theme.

I recommend listening to Sandy Denny and Fairport Convention’s version of “Percy’s Song”—available on YouTube—which I recently stumbled upon. As I listened to Denny’s lovely voice and her interpretation of the lyrics, I felt the force of Dylan’s argument-in-song. Denny’s performance goes back in time, calling forth the original source materials. Simultaneously, this 1969 recording seems eerily prescient, drawing upon universal themes of injustice and the finality of misguided legal and political judgments that remain equally compelling today.

‘Blind Willie McTell’

“Blind Willie McTell” (1983) is another of Dylan’s alchemical adaptations. It is a visionary song, yet remarkably simple in its structure: Dylan presents a tableaux of hauntingly familiar images layered atop one another, every verse returning to the repetitive refrain: “And I know no one can sing the blues like Blind Willie McTell.” It is also, like “Percy’s Song,” an adaptation. Dylan uses the traditional American melody of “St. James Infirmary.” The song works because of—not in spite of—the familiar melody, the imagery and the structured repetitions of the refrain, glued together by the feelings in Dylan’s voice and the universality of the theme about our often-defeated longings for justice.

The song gives Dylan’s testimony about injustice and the black experience in America. Yet Dylan makes few explicit judgments; he merely places familiar images that become visceral and haunting when juxtaposed in the song. He relies upon this borrowed melody from “St. James Infirmary” and the structured repetition of the refrain to work on the listener, evoking emotion.

In the song, Dylan sits “gazing out the window of the St. James Hotel.” First, he sees a sign saying “this land is condemned, all the way from New Orleans to Jerusalem.” Then he sees “plantations burning, hear[s] the cracking of the whips, smell[s] that sweet magnolia blooming, [and] see[s] the ghost of slavery ships.” Next, he sees “a woman by the river with some fine young handsome man ... dressed up like a squire, bootlegged whiskey in his hand.” Then “a chain gang on the highway, I can hear those rebels yell, and I know no one can sing the blues like Blind Willie McTell.”

As in the darkness and fatalism of the Child ballads, Dylan finally suggests meaning for the imagery:

Well, God is in His heaven

And we all want what’s His

But power and greed and corruptible seed

Seem to be all there is . . .

Several months ago, I listened to “Blind Willie McTell” (Dylan’s own electric version on YouTube with Mick Taylor playing a powerful slide guitar), as a soundtrack to images on the nightly news—immigrant families separated at the border, President Donald Trump’s proposed wall and the consequences of the government shutdown.

Like a movie score, Dylan’s song enabled me to respond emotionally to the recycled images on the television screen as if I was seeing them anew, perhaps for the first time.

Three Lessons for Lawyers

1. Adaptation: Listen like an artist and fearlessly incorporate what works into your own oral storytelling practice. Study the work of other lawyer-storytellers (just as Dylan studied his musical predecessors) and other popular storytellers, including musicians. And save citations to authority for your written legal briefs.

2. Structured repetition: Use structured repetitions purposefully—just as Dylan returns to his refrains. In oral storytelling, emotional intensity and meaning itself are typically built upon purposeful repetition.

3. Universal themes: Whenever possible, draw upon the universal themes that provide the narrative glue and story-drive of many folk tales and of many courtroom stories, too. These themes include our longing for justice and our inexpressible grief when the law fails its promise of justice for all.

Philip N. Meyer, a professor at Vermont Law School, is the author of Storytelling for Lawyers. This article was published in the April 2019 ABA Journal magazine with the title "Dylan's Songs: Lawyers can learn from this folk master, who cleverly retrofits traditional melodies."